Causes of the Civil War has been rereleased and is available in our bookstore today! Interested in purchasing classroom bundles? Discounted pricing is available for teachers

Teaching American History’s philosophy is that the best way to learn American history is to read the words of those who lived it. That’s why we maintain an extensive database of original documents. This approach also drives the content in our graduate courses, One Day Seminars, Online Teacher Webinars, and Weekend Teacher Seminars. TAH scholars don’t discuss specific teaching strategies in these programs, but teachers often discuss them within the context of the topic.

It was in one such conversation that I learned a method of teaching Abraham Lincoln’s Fragment on the Constitution and Union, which asks students to apply the principles of the Declaration of Independence, its relationship to the Constitution of the United States, and the purpose of the Union over the course of an entire year.

Lincoln received a letter from his former congressional colleague, Alexander Stephens, during the long secession winter of 1860–61. Stephens quoted Proverbs 25:1, “A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver” (KJV). He wrote that a word of reassurance to the Southern slave states from President-elect Lincoln would be “the word fitly spoken.” It might temper the secession movement and avert civil war.

Though Lincoln never replied to Stephens, he seized on the biblical verse but asserted that the nation already possessed the “apple of gold” provided by “the word fitly spoken.” It was the principle of “liberty to all” which “clears the path for all—gives hope to all—and by consequence, enterprise, and industry to all….” Still, Lincoln went further. The apple of gold, the principle of liberty to all, was protected by the Constitution and the Union, he noted. Indeed, the most fundamental purpose of the Constitution and the Union was to protect that principle, that “apple of gold.”

My fellow seminar participant told us she used a cardboard apple of gold on a bulletin board in her classroom and challenged students to discuss whether a policy, concept, political speech, or law faithfully represented the “Apple of Gold.” The freedoms in the Bill of Rights, for example, or American exceptionalism, Manifest Destiny, social and political equality for women and racial minorities, and immigration policy.

I thought this idea was brilliant and couldn’t wait to use it with my students. I convinced my principal to purchase a large bulletin board for my classroom and persuaded a talented art student to create a cardboard Apple of Gold, which I placed in the center of the board. We pretended the aluminum sides of the bulletin board comprised the frame of silver, the Constitution, and the Union that protected the Apple of Gold, the principle of liberty to all found in the Declaration of Independence.

I taught this lesson on the first day of class in my AP US History classes. I taught it in my regular courses when teaching the American Revolution. And I used it repeatedly when discussing the events of the 1850s that culminated in secession and the Civil War. And I have evidence that it works! One year, I overheard students leaving my class after this lesson saying to one another, “That was the best lesson ever!” Music to a teacher’s ears.

Over the course of the year, the board became an interactive bulletin board. We might discuss Manifest Destiny, for example, and I would ask the students whether that concept aligns with the Apple of Gold or violates it. Students took a Post-it note, wrote “Manifest Destiny” on it, initialed their note, and placed it either on or off the Apple of Gold. Some students said it fit because it encouraged settlement of the West by the citizens of the United States, the people the government was sworn to protect. Other students argued it violated the liberty of indigenous people, so it did not belong on the Apple of Gold.

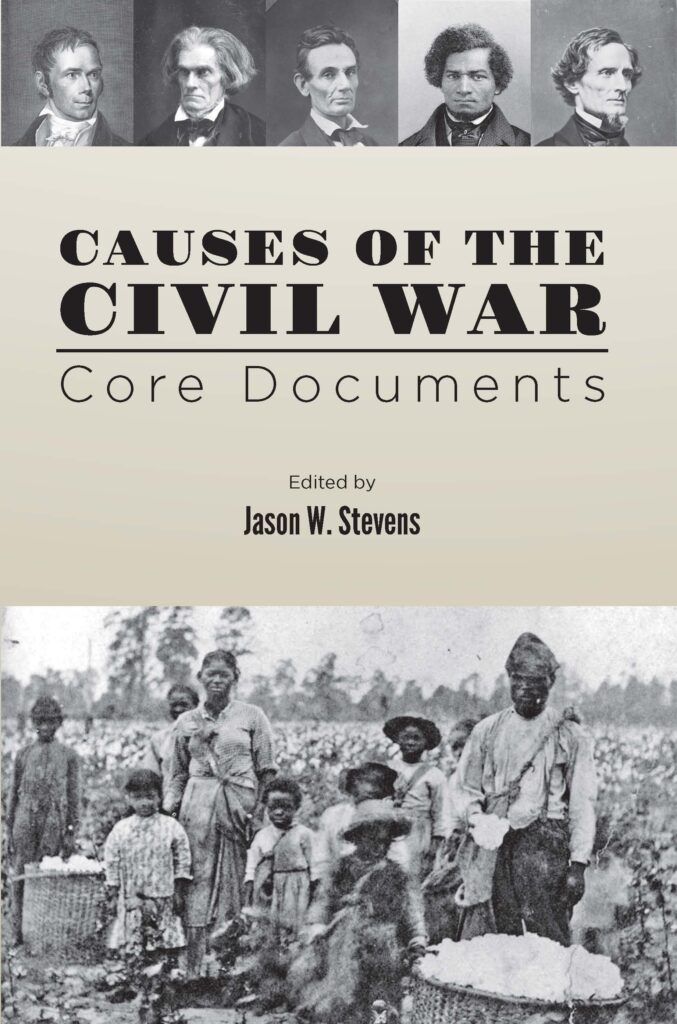

Causes of the Civil War: A Classroom Resource

Teaching American History re-released its Core Document Collection volume, Causes of the Civil War, in early September 2025. This volume of original documents, curated by Dr. Jason W. Stevens, includes an introduction, 26 significant documents from the antebellum era, a Thematic Table of Contents, and Study Questions for each document. Like most teachers, I wish I had the time to discuss every one of these primary sources with my students. Given the time constraints we all face, I assigned Thomas Jefferson’s letter to John Holmes when teaching the Missouri Compromise. For insight into the debate over slavery, I assigned Frederick Douglass’s speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” and excerpts from the Dred Scott decision. These three documents are in the CDC Causes of the Civil War volume.

However, I always assigned two documents to teach about secession: the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina, and Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address. My South Carolina students were interested in the state’s justifications for seceding from the Union. Many of them anxiously defended their home state after reading its claim that the northern anti-slavery states had violated the “two great principles asserted by the colonies” during the American Revolution, … “namely; the right of the state to govern itself; and the right of the people to abolish a government when it becomes destructive of the ends for which it was instituted.”

What’s missing, I asked them. Are these the only two principles asserted in the Declaration of Independence when we told King George III, “Enough is enough, it’s time for the colonies to become an independent nation?” Are there any other “self-evident truths?” Sometimes, it took a few minutes, and sometimes I wandered over to my bulletin board and pointed to the Apple of Gold before someone said, “All men are created equal, that’s what’s missing.”

Next, the students considered Lincoln’s assertion in his First Inaugural Address that “plainly, secession is the essence of anarchy.” Many students are perplexed by Lincoln’s decision to resist secession militarily. They wonder why Lincoln didn’t simply let the Southern slave states leave the Union. Why try to preserve a Union with people unwilling to abandon the enslavement of another race of people? I challenged those students to consider the presidential oath of office and Lincoln’s perspective on the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. Each president swears to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.” Would Lincoln be abandoning forever the cause of the four million enslaved people in the South, the promise of the Apple of Gold the Declaration offered them if he did not fight to preserve the Union?

Of course, my take on the documents Dr. Stevens included in Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection, Causes of the Civil War is just one teacher’s opinion. The volume’s Thematic Table of Contents suggests other topics that teachers should consider, such as Pro and Anti-slavery Arguments, the Compromises of 1820 and 1850, and Popular Sovereignty. Whichever of these themes a teacher chooses to pursue, the Apple of Gold classroom activity could be used with every document in Stevens’s well-considered collection.

Get your copy of Causes of the Civil War here

Ray Tyler is a retired U.S. History and Government teacher and former Teacher Program Manager for Teaching American History. The 2014 recipient of the James Madison Fellowship (SC), Ray works as a TAH host for our content professional development programs, contributes to the We the Teachers blog, and writes introductions and study questions for some of the documents on the TAH website. Ray and his former student, Rachel Black, co-author American History Café, a Substack Newsletter featuring stories of ordinary Americans doing extra-ordinary things.