A week or so ago, legendary BBC broadcaster David “Ram Jam” Rodigan stepped to the front of the stage at Nostrand Avenue’s Crown Hill Theatre and mesmerized an audience of devoted reggae fans by recounting the day in 1980 when he bustled up the stairs at Island records’ London offices and almost ran into: “Robert. Nesta. Marley…I froze.”

“I couldn’t believe it. I junked protocol and I said, ‘Please, Mr. Marley, will you come on my show tomorrow night?’” he continued breathlessly.”He said, ‘Yes, I will.’ He was with [Wailers’ bassist and bandleader] Aston “Family Man” Barrett and the both of them said, ‘We just finished working on our new song, would you like to come and hear it?’ We go back upstairs to the listening room at Island Records. He takes his cassette out of his jacket, puts it in, and presses play.”

By the time Rodigan himself hit play on the instantly recognizable rhythm guitar and cuíca groove of Marley’s club-friendy hit “Could You Be Loved,” the Brooklyn crowd exploded in a raucous forward, but not before he shared one last jewel. “At the end [Bob] turns to me and says, ‘Is that mix suitable for FM radio in New York?’ He was specific about the type of radio and he was specific about New York City.”

Marley, of course, had precious little time on Earth ahead of him at the moment of this chance encounter, but he did get to realize his dream of conquering the Big Apple. In September of that year, he sold out two nights at Madison Square Garden on a bill shared with The Commodores and Kurtis Blow. The very next day, he collapsed while jogging in Central Park, signaling an imminent end to his final tour. But even if reggae’s undisputed king was not around to see it, Jamaican music’s invasion of New York was just getting warmed up.

Waves of the Island’s most talented singers, deejays, and selectors relocated to NYC permanently or semi-permanently to perform on mobile reggae sound systems like Addie’s Hi-Fi, do business with Hyman Wright’s Jah Life record label on Utica Avenue and record at HC&F studios in Long Island, a steady stream of creative migration that in the ‘80s and ‘90s would become a flood, transforming the borough of Brooklyn, in particular, with a host of reggae venues, record shops and studios that ultimately helped East Flatbush earn its official designation as Little Caribbean and Brooklyn’s unofficial designation as Jamaica’s “15th Parish.” By the mid-’80s it was expected that the announcement of any reggae event in New York would culminate in the ritual phrase “All roads lead to [ __ venue] inside Fun City – Brooklyn!”

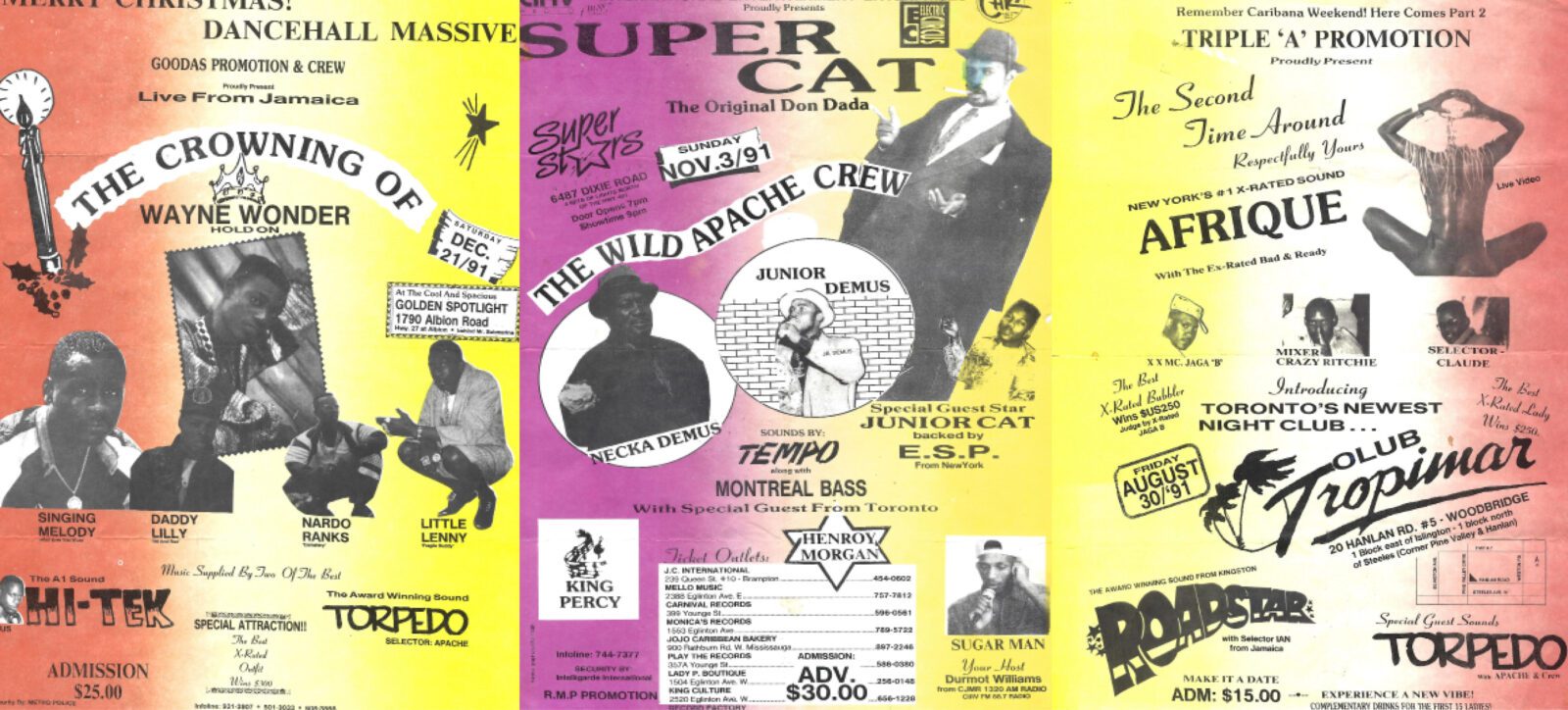

As a reggae broadcaster on BBC, Capital Radio and Kiss.fm David “Ram Jam” Rodigan has one of the deepest “dub boxes”—a catalog of custom recordings by in-demand artists—in the business (Courtesy of Walshy Fire)

The rest of that evening was filled with tales of many such unforgettable nights in Brooklyn as each musical selection—many of them one-of-a-kind recordings cut straight to dubplate by reggae giants like Beres Hammond and Dennis Brown—was prefaced with historical context from Rodigan and his co-headliner DJ Rory (formerly of the influential Stone Love sound system) not to mention openers Max Glazer of Federation sound and DJ Roy of Road International, known to many Brooklynites as the voice of Irie Jam radio. Roy, in particular, ran down an exhaustive roll call of the venues that “all roads led to” on one night or another, including but not limited toL The Q Club, Love People One, Empire E, Village Hut, Pyramid International, Legend, Underground, The Ark, Callaloo and—according to Roy, the real badman club—Colonial Mansion. One Brooklyn venue, however, came up again and again as the site of reggae history: the Biltmore Ballroom at 2230 Church Avenue.

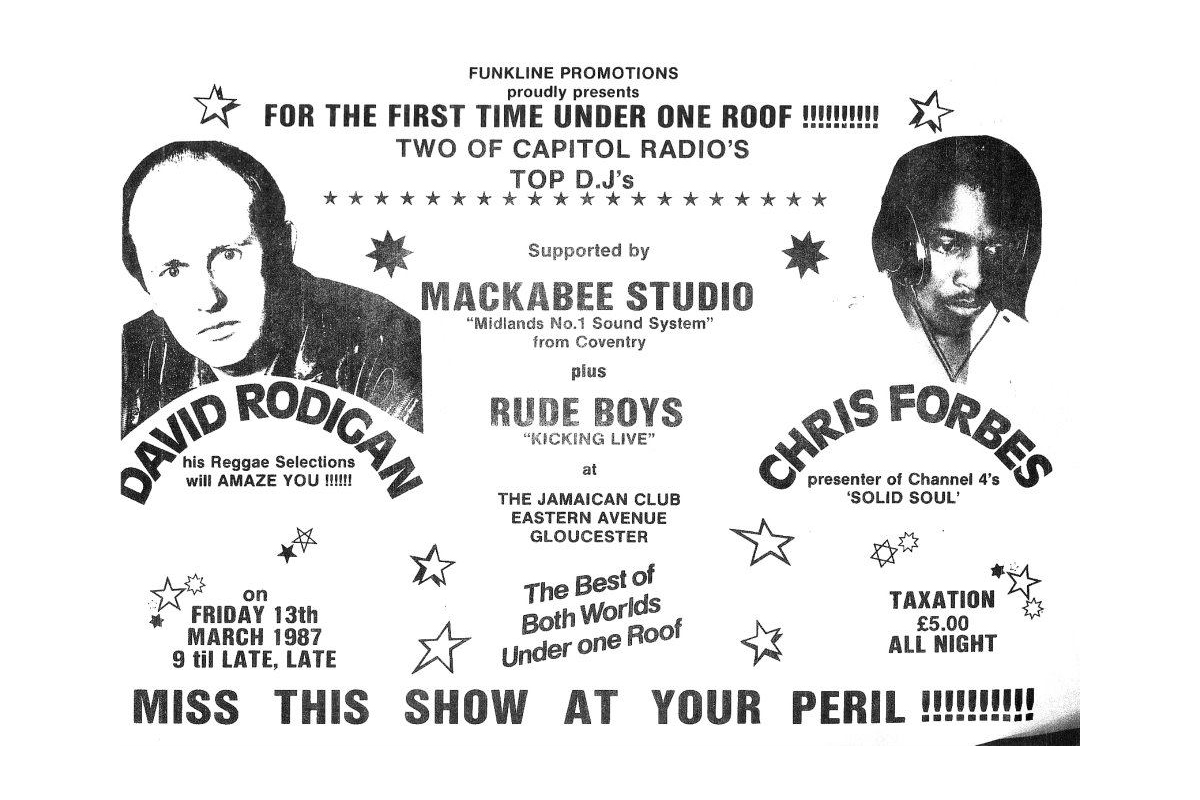

Brooklyn venues like the Biltmore Ballroom and mobile sound systems like King Addie’s and Afrique SoundStation played an essential role in bringing artists like Bounty Killer, Buju Banton, and Sean Paul to a global audience.(Courtesy of Walshy Fire)

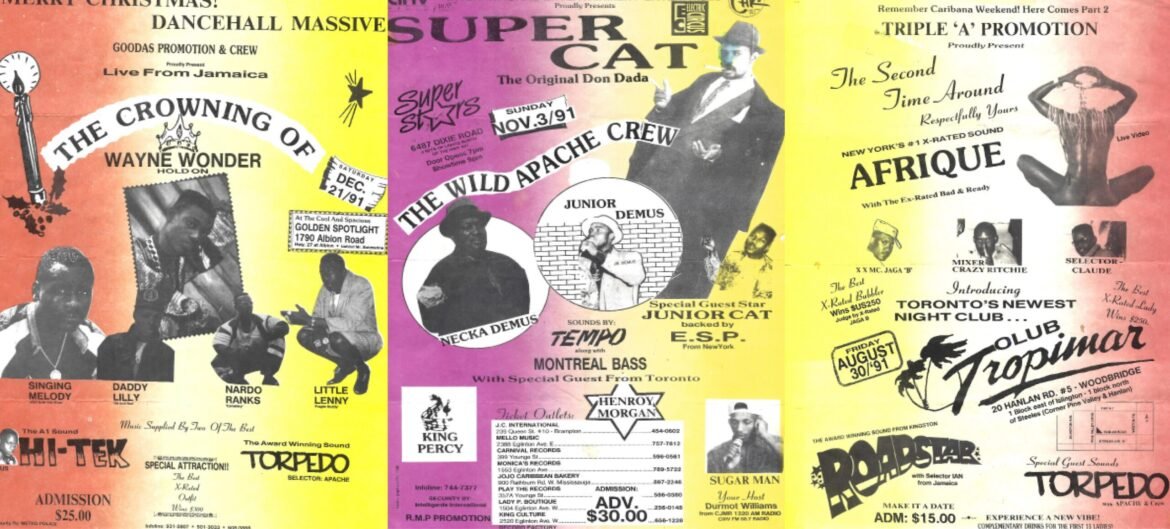

Many of these hallowed addresses had long since been replaced by other businesses by the time they could be typed into Google Maps, but thanks to a new coffee-table style book from Major Lazer’s sole Jamaican member Walshy Fire, they are no longer just names to invoke on mic ‘til they echo into silence. Art Of Dancehall—published this month by Rizzoli Books—treats the technicolor flyers and posters used to promote these events as the art pieces they are, visual traces of reggae from the genre’s early days up until the turn of the millennium, documenting the visual flair of a design vocabulary that is uniquely Jamaican, no matter what continent it’s wheat-pasted across.

“I’m originally from the Halfway tree part of Molynes Road [in Kingston, Jamaica]…” Walshy says of his inspiration for the collection, speaking by phone from the hotel in Spain where he’s just checked in and begun preparing for a DJ gig. “If anybody knows anything about Halfway tree…that’s where it goes down. It’s like a cultural hub. You got all the mini-vans with names like “Terminator” and “Roadstar,” loud speakers playing the latest music. You had all the cassette guys like Jack Sowah, Skunkman, and Cassette Peter at the arcade. My love for cassette artwork actually came before the flyers. The way those guys used to write the names of the sounds was just so cool. I remember showing that off in junior high school. My first big cassette was Buju Banton, Stone Love 1992. I knew I had gold in my hand; I literally could show the artwork on that cassette tape to anybody and they would be like ‘Ok, whatever’s on that needs to go into a national treasury.’”

In the 1990s, Stone Love Movement became one of the first Jamaican sounds to have franchises in New York and London, boasting of their ability to play three events on three different continents in one night. (Courtesy of Walshy Fire)

Soon young Walshy was selling tapes himself, the first steps towards a globe-spanning DJ career, as well as his personal treasury of visual dancehall culture that is partially represented in the book. Although he is best known as a native of Jamaica and current resident of Miami, Walshy, born Leighton Walsh, did a stint in Brooklyn himself in the early ‘00s, at which time he could be found juggling selections in the reggae room at Beat Street records on Fulton Mall. Not surprisingly, Art of Dancehall traces reggae’s global reach with sections covering Jamaica, UK, Canada, Japan and—in the USA section—a healthy dose of Brooklyn.

“I first came to Brooklyn in 1994,” Walshy continues. “When I got to Clark Atlanta [University] I meet all these Brooklyn guys who go home to New York for Christmas. My first time going to Brooklyn was Christmas ‘94. It was still Biltmore Ballroom days but [when I went] it was just a regular juggling night, nothing to compare with Jamaica. But…I met a girl–in a huge Northface bubble jacket—who I ended up falling in love with. So now I’m trying to talk to this girl and I’m like, ‘I gotta go back to New York’. So I spent a good portion of that following summer sleeping on friends’ floors. I was staying on 90-something and Rutland road [during Labor day weekend’s West Indian Carnival] and my friend Trini was like, ‘Yo there’s a block party in the ‘90s, we’re gonna walk over.’”

“Bro,” Walshy pauses for dramatic effect. “I never had a moment like this before and I’ve rarely had a moment after where I was looking at dancehall in its absolute peak and I knew it. There was a lot of sounds playing and it was pa-a-a-cked; thousands of people were at this block party. A sound system called “Thunderbolt” started to play and I have never in my life seen gunshots [let off in the air] like that. It was that era of Brooklyn dancehall. The song that got the biggest salute was the Snow “Anything For You” remix!”

In 1995, the white Canadian reggae singjay Snow put his major label budget to good use, assembling an “All-Star Cast Remix” for the 12” release of his dancehall duet with Nadine Sutherland, a posse cut of the genre’s hottest deejays, including Beenie Man, Buju Banton, Louie Culture and Terror Fabulous. “That song played for one hour and the gunshots were insane. You could see them sparking it on the roof. This is the wildest thing I’ve ever experienced and I love it. I’m just standing there like, ‘Yo this is just another night for these guys.’”

“I just fell in love with Brooklyn after that,” he concludes. “I’ve been to the World Clashes. I’ve been to the big dances at Amazura, but none will ever out-peak dancehall in Jamaica or that mid-’90s era of Brooklyn. Like seeing Earth Ruler…peak Earth Ruler? It’s kinda hard to go into any other decade and be like, ‘This is better than that.’”

Lee Major, one of the top selectors for the Brooklyn-based Earth Ruler, was in fact a major source for the flyers in the USA section. Like many DJs, his collection started with the first flyer that bore his own name. “I held on to it for dear life!” he laughs now, in remembrance. “I even slept with that flyer.”

But his collection soon grew to encompass a storage unit full of posters, handbills, and videos (some of which were featured in the recent documentary Bad Like Brooklyn Dancehall) that documented the thriving subculture. “Big up to Utica Printing and Irie Myrie,” he says of Brooklyn designer Errol Myrie, who gave New York flyers their distinct look—part photocopy collage, part Marvel comics. “He’s one of them that changed the game as far as graphics.”

When asked what individual events from the era stand the test of time, he replies, without hesitation, “Biltmore. The Buju Banton show that Supa Claude from Afrique Soundstation kept in Brooklyn was phenomenal. That event was humongous—that was the first time Buju Banton came to New York City [in 1992]. They had helicopters, there was a S.W.A.T. team and they closed off the whole of Church Avenue, because they never seen so many people out there for a reggae entertainer at a venue like Biltmore as came out to see Buju when he first came to America.”

There is another event that stands out, a flyer which Walshy specifically requested to include in the book, that Major took part in himself. “Earth Ruler Sound vs Addie’s. Well, that was definitely a historical moment for the dancehall fraternity. At that time, Addie’s was the most dominant sound in the culture in New York, and, if I can say honestly? The world.”

Addie’s Hi-Fi, a mobile sound system which was re-christened King Addie’s when they bested Downbeat in a clash billed as the “Battle For New York,” was one of the major draws for talent that made Brooklyn Fun City. In particular, the migration of selector Danny Dread, a revered figure who spans the eras of reggae from the days when he would receive pre-release tunes direct from the likes of Bob Marley and King Tubby right up until today, helped to put Addie’s and Brooklyn on the map. Jamaican artists like Super Cat, Nicodemus, and Tenor Saw began passing through dances held by Addie’s to pick up the mic while Danny mixed and soon became permanently affiliated with both Addie’s and the borough.

By contrast, “Earth Ruler was considered a young sound,” Major recalls. “It was like no other dance in Biltmore Ballroom that I can recall in the history books, because we changed the culture of dancehall in New York. Before that it was Clarks shoes and double-breasted suits, we came with that American swag of baggy jeans and Tommy Hilfiger.” It also marked a change in the style of mixing by selectors. “Danny Dread—with due respect for the superhero—was like, put record on, make it play almost all the way to the end, while Earth Ruler is one of the sounds that contributed to that speed juggling,” a technique for playing multiple records or dubs just one beat, and in fast succession.

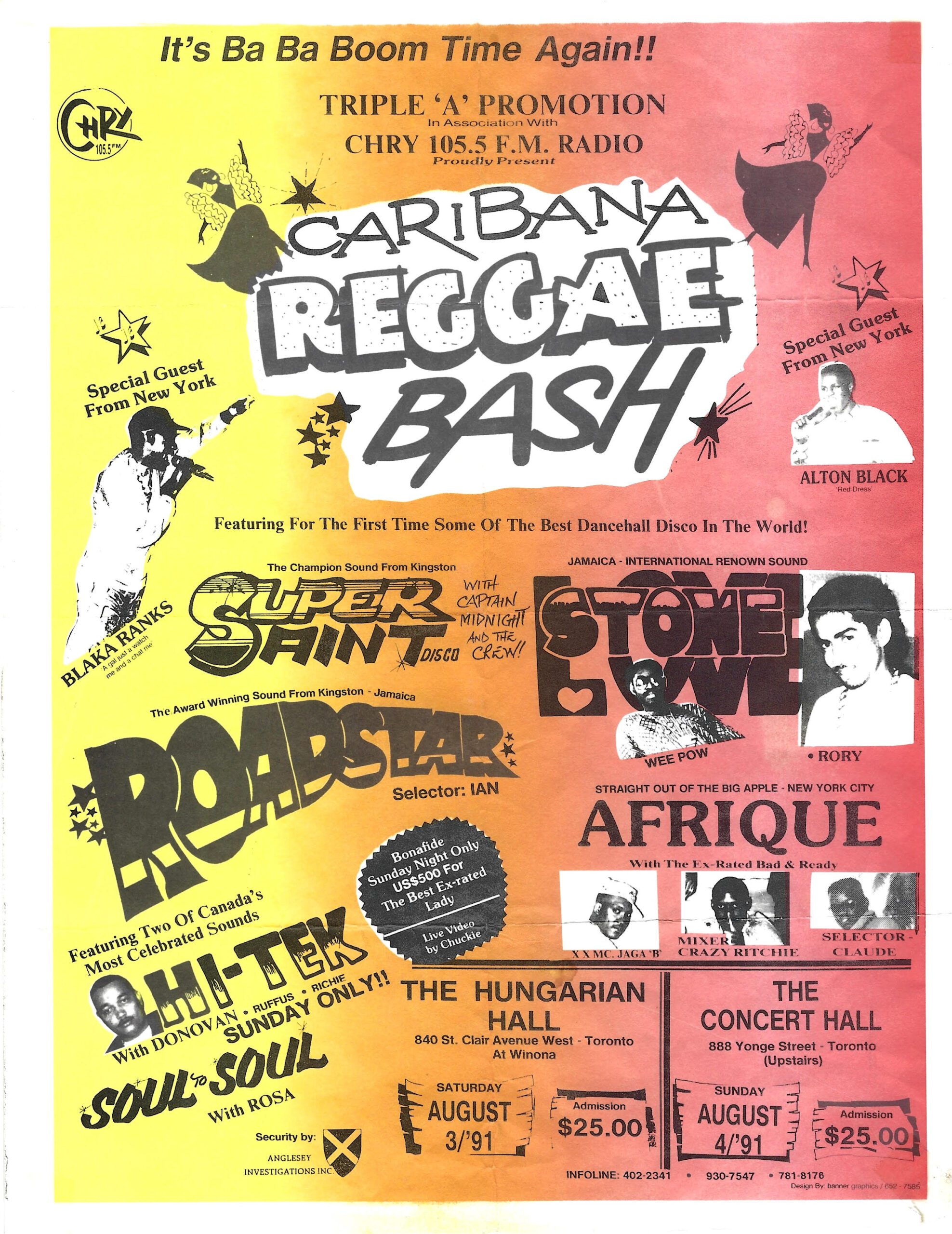

Brooklyn-based reggae selectors like Danny Dread, Baby Face and Tony Matterhorn were stars in their own right, every bit as famous as the singers and deejays who often performed at their events. (Courtesy of Walshy Fire)

King Addie’s reign was far from over, however. Under Danny’s tutelage, Brooklyn-bred selectors Baby Face and Tony Matterhorn would become world famous. Matterhorn’s clash with top Jamaican sound Killamanjaro, helmed by Ricky Trooper, is widely regarded as the greatest clash of all time. Baby Face, for his part, can be credited with bringing a young Sean Paul to perform in New York for the first time. Paul told this story himself, recalling how he crashed on the couch at Addie’s HQ on the corner of Livonia and Pennsylvania in a public talk held at the Brooklyn Public Library moderated by Max Glazer.

“I wasn’t there to witness firsthand many of the things I would consider legendary dancehall nights in Brooklyn,” Glazer relates in the days after his opening set at the Crown Hill show. “But that’s the energy we tried to channel for the Federation 25th Anniversary concert. That’s why it was really important to have artists like Red Fox and Screechy Dan on the bill, who are such cornerstones of Brooklyn dancehall. There’s one particular clip of them performing with Rayvon at Club Warehouse in 1998. I get chills just thinking about it, because it’s like the most perfect capture of unadulterated dancehall energy.”

Indeed, as the Federation showcase underscores, Brooklyn is still Fun City, even if it’s no longer the Temporary Autonomous Zone Walshy Fire visited in the ‘90s.

“I like what I see happening in the soundclash space right now,” says documentary filmmaker Christine Coley of the current landscape for reggae sound systems. Coley is currently completing her film degree, but has also assisted numerous East Coast sounds—notably Addie’s—with their publicity via her marketing firm Impulse Nation. “Everything in life happens in cycles. It cycles up, it cycles down…there’s always a changing of the guard. But people find ways to persist, people find ways to invent.” Coley notes the popularity of the Beenie Man vs. Bounty Killer Verzuz and Red Bull’s annual Culture Clash as contemporary indicators of soundclash’s popular appeal. Appropriately, when pressed for her own great moments in Brooklyn reggae, she includes a more recent one.

“I don’t know if you know [sound system] King Shine, with selector Jimmy Spliff? I like that clash [against Addie’s] because the turning point in that dance for me was when King Shine played a dub from Koffee and then [Addie’s selector] Kingpin answered with a custom Lila Ike dub. And, I mean, it just tore down the place. I can’t remember in recent times when two female artists were put head-to-head like that. Being a woman in the business myself, I feel like that was a great moment in the culture.”

There may be more great moments yet to come. This very weekend, dancehall star Vybz Kartel headlines his first stateside show in 15 years at Barclays Center, while on the neighboring planet of Queens, reggae’s pioneering woman deejay Sister Nancy will be appearing alongside Danny Dread himself at a Record Store Day event Saturday. Beenie Man is also slated to perform at UBS Arena in May, and even the Rodigan and Rory show at Crown Hill Theatre is just the first installment of a “Star Selector” series.

“It’s 2025 and all our pillars in dancehall are going to be touring America,” says Coley. “I believe this is going to be an explosive year for our genre.” If she’s right, Walshy Fire may just need to start on his next book of dancehall history soon.

The post Rudeboy, Remember: Walshy Fire’s ‘Art of Dancehall’ appeared first on BKMAG.