You have full access to this article via your institution.

The name Asilomar has become a metaphor for problem-solving in science and society.Credit: Stephen B. Goodwin/Shutterstock

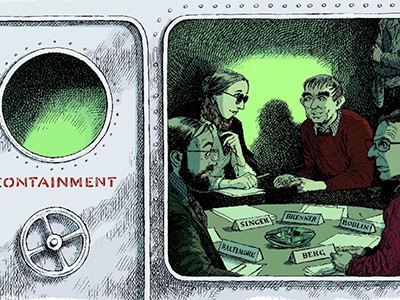

In 2008, Nature published a six-part essay series called Meetings that Changed the World. One of our choices was the International Congress on Recombinant DNA Molecules, held in February 1975 at the Asilomar Conference Center near Monterey, California — and known, ever since, as the Asilomar conference1. This meeting brought a temporary moratorium to an end and established the basis for rules to ensure that research on genetically modified organisms minimizes risks.

Delegates proposed risk-based principles to determine, for example, which experiments could be done on an open bench and which required physical containment. These were accepted by the US National Institutes of Health the following year, allowing research in the field to resume.

The anniversary of the conference, undoubtedly a landmark event for science and society, offers an opportunity to think about what it might take to move the dial on analogous issues today. It will almost certainly take much more than the single Asilomar meeting of some 140 scientists, government officials, lawyers and journalists.

Asilomar 1975: DNA modification secured

Fifty years ago, the concept that you could snip genes from the DNA of almost any organism and insert them into a virus or bacterium in such a way that they could be copied each time the microorganism reproduced was in its infancy. DNA modification came with great potential for fields such as agriculture and medicine, and is now a complex and precise science. Just this week, David Liu at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was awarded the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for inventing precision gene-editing tools2,3.

But in the 1970s, the then-new science was beset by concerns. One was that “introduced genes could change normally innocuous microbes into cancer-causing agents”, according to biochemist Paul Berg, one of the conference’s main organizers and author of the 2008 essay. At the time, Berg was studying the genetics of infection and, in particular, whether simian virus 40 could produce tumours in rodents. In 1974, he had led a committee reporting to the US National Academy of Sciences that had recommended pausing potentially hazardous experiments, pending an international conference to discuss the next steps.

Much ink has been devoted to reflecting on this event — in terms of both what was discussed and what (and who) was left out. At a ‘spirit of Asilomar’ conference in February, it was pointed out that the original meeting lacked participation from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

And although it was not openly discussed at Asilomar, the desire to lift the moratorium was driven, in part, by the potential for universities to profit from the technology, as Matthew Cobb, a zoologist at the University of Manchester, UK, has explained4. It didn’t take long for that discussion to become mainstream. By 1980, a decision of the US Supreme Court enabled DNA patenting, and a US federal law was passed granting permission for universities to hold intellectual-property rights and license patents for federally funded discoveries and inventions. This fuelled the growth of today’s many science-based corporations.

But Asilomar’s reach goes further. It is often invoked in relation to the organization of conferences in areas in which there are concerns about science, innovation and public policy. However, if Asilomar were to be held today, the process would be very different from that of 1975. There wouldn’t be only one meeting, and there would be much more involvement of research communities from LMICs, as well as representatives from civil society, businesses, public officials, including regulators, and other stakeholders.

Such an event would also be harder to organize. As Berg wrote in 2008, “In the 1970s, most of the scientists engaged in recombinant DNA research were working in public institutions and were therefore able to get together and voice opinions without having to look over their shoulders” but “many scientists now work for private companies where commercial considerations are paramount”.

The Asilomar conference came about as a result of scientists taking responsibility, at an early stage, for the risks inherent in their work, and making an effort to think about regulations to minimize the harm that such work could cause. Today’s researchers should draw inspiration from the organizers’ courage and foresight, and build on Asilomar’s foundations by making such events inclusive.