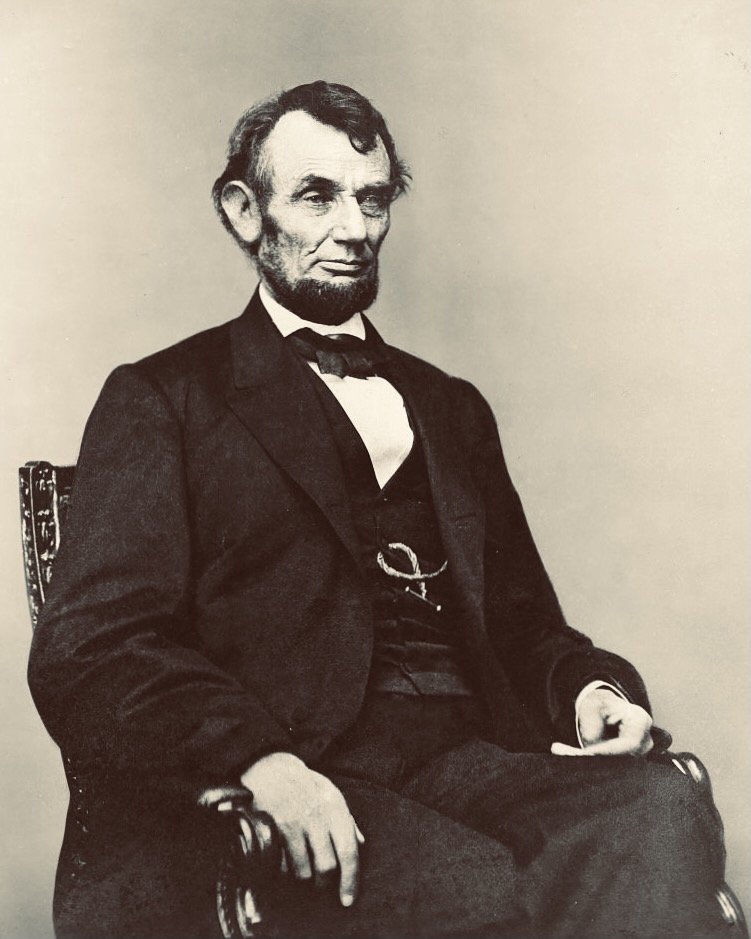

One of the many letters Abraham Lincoln received after being elected president in November 1860 was from Alexander Stephens, a former congressional colleague of Lincoln and the future Vice-President of the Confederacy. He urged Lincoln to make a public statement regarding his intentions as president. It would be, Stephens wrote, “the word fitly spoken” that might “save our common country.” Lincoln deliberated on the phrase and jotted down some thoughts on the essential purpose of the Constitution and the Union.

Lincoln’s notes are preserved in a document historians call the Fragment on the Constitution and Union. Lincoln believed the “word fitly spoken” already existed. “It is the principle of “liberty to all”—the principle that clears the path for all—gives hope to all—…, enterprise and industry to all.” The “word fitly spoken” is the promise of the Declaration of Independence, liberty and equality for all people. An “apple of gold in a frame of silver.”

If Lincoln was right, if “liberty to all” was “the word fitly spoken,” why did he claim in his first inaugural address; “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Why not immediately declare liberty for the enslaved people in the South? Why wait so long to issue the Emancipation Proclamation?

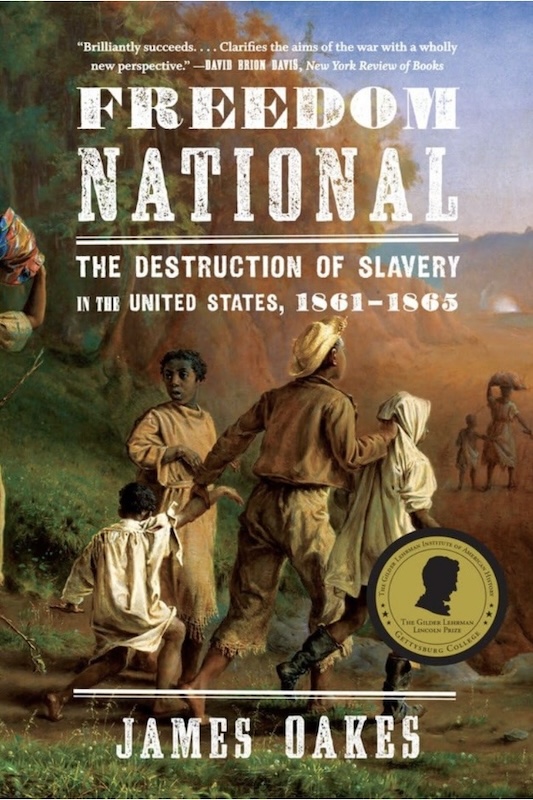

The answer, according to historian James Oakes, in his outstanding book Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1860-1865, is that emancipation was not “the singular act of a singular individual” as many Americans assume. The actual emancipation story is far more complex.

PEACETIME EMANCIPATION

Oakes argues for a broader understanding of the context of the Emancipation Proclamation. In the decades preceding the Civil War, anti-slavery editors, politicians, and abolitionists developed a legal and constitutional theory that guided their emancipation strategy.

As early as 1851, Republicans like Senator Henry Wilson (MA) were articulating a peacetime emancipation theory that insisted Congress could legislate against slavery in territory under its domain. “We shall arrest the extension of slavery” in the territories, Wilson said. “… and blot out slavery in the National Capital. We shall surround the slave States with a cordon of free States.” According to this theory, slavery existed in the United States because some states protected “the peculiar institution” with state legislation. Freedom, however, was national. The Constitution was not a pro-slavery document. Lincoln, congressional Republicans, and many abolitionists assumed this “cordon of freedom” would inevitably lead the slave states to abandon slavery on their accord.

WARTIME EMANCIPATION

War changed everything. Military emancipation was constitutional as necessary to save the Union from a rebellion. With southerners absent from Congress, Republicans quickly built the “cordon of freedom” with limited opposition from northern Democrats. Within three months of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Republicans banned slavery in the western territories and Washington, DC, and blocked federal enforcement of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause.

In August 1861, Lincoln signed the 1st Confiscation Act, authorizing the military to reject enslavers efforts to reclaim their so-called “property.” Union officers and soldiers could not encourage enslaved people to flee bondage but were not required to return those who “self-emancipated.” Lincoln signed the 2nd Confiscation Act on July 17, 1862. Now Lincoln and Congress were committed to a military emancipation in addition to their “cordon of freedom” peacetime strategy.

Lincoln quoted from the 2nd Confiscation Act when he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. Under the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation military officers and men could entice slaves to escape on the promise of freedom. The disloyal states had one hundred days to reenter the Union, or their slaves would be “forever free.”

The Final Emancipation Proclamation, signed on January 1, 1863, quoted Sections 9 and 10 of the 2nd Confiscation Act verbatim. In his First Inaugural Address, Lincoln acknowledged that a president did not have “the power to interfere with slavery” where it existed. But he did not say that a president lacked that power during a civil insurrection. With the onset of war and the authorization of Congress, the commander-in-chief exercised that power.

I wish I could hear a recording of Abraham Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural Address. When he said, “that all knew” slavery was “somehow” the cause of the war did he emphasize “somehow”? He said neither side expected “the cause of the conflict might cease” before the war ended. Yet, he knew his administration implemented peacetime emancipation upon assuming office and military emancipation after the war started. And he knew their plan succeeded. It is difficult to believe he was surprised at the outcome.

For more classroom-ready Lincoln documents, please see our CDC volume, Abraham Lincoln, available for purchase or download from our bookstore.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.