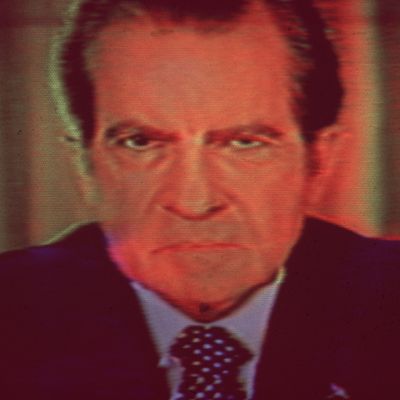

The poor, persecuted 37th president.

Photo: Ernst Haas/Getty Images

In the years between Richard Nixon’s resignation as president in 1974 and his death in 1994, there was plenty of time for reconsiderations of his career, his crimes, and his legacy. Biographers often focused on his complicated character and his inner demons. As Republicans turned to the more politically palatable but also more reactionary Reagan style of conservatism, Democrats often noted that Nixon wasn’t all bad when it came to domestic policy; he signed the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, appointed the Supreme Court justice who wrote Roe v. Wade, and even committed the supreme conservative ideological heresy of imposing wage and price controls. Even more often, admirers from various backgrounds dwelled on what Nixon himself cared most about: his foreign-policy work, most notably détente with the Soviet Union and his “opening” to China.

When I first read presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy’s argument that Nixon was actually the progenitor of Donald Trump’s “America First” approach to foreign policy, I interpreted it as a typically quirky variation on the tradition of looking past Watergate to Nixon’s international accomplishments, such as they were. While I mocked Ramaswamy’s take on what Nixon actually did and stood for, I didn’t realize I was hitting the tip of an iceberg of MAGA love for the Tricky One that goes far beyond his policy legacy to the very thing most of his advisers want to ignore or minimize: Watergate.

As Ian Ward explained at Politico Magazine, Nixon is making quite the comeback on the contemporary political right:

Long condemned by both Democrats and Republicans as the “crook” that he infamously swore not to be, Nixon is reemerging in some conservative circles as a paragon of populist power, a noble warrior who was unjustly consigned to the black list of American history.

Across the right-of-center media sphere, examples of Nixonmania abound. Online, popular conservative activists are studying the history of Nixon’s presidency as a “blueprint for counter-revolution” in the 21st century. In the pages of small conservative magazines, readers can meet the “New Nixonians” who are studying up on Nixon’s foreign policy prowess. On TikTok, users can scroll through meme-ified homages to Nixon. And in the weirdest (and most irony laden) corners of the internet, Nixon stans are even swooning over the former president’s swarthy good looks.

That was a revelation to me as someone whose grandmother voted against Nixon three times because she didn’t like his nose.

But the Nixon cult being constructed in MAGA-land is dead serious, and what makes it deadly serious is the ex post facto justification — even glorification — of the abuses of power that most Nixon fans don’t want to discuss. As Ward reports, one of the chief engineers of the new Nixon fad is the young conservative activist and provocateur Christopher Rufo, who recently wrote an appreciation of Nixon’s uninhibited and often unconstitutional war with the leftists of his time in City Journal:

As the radical left-wing factions asserted themselves in the universities and in the streets, voters cast their presidential ballots for former vice president Richard Milhous Nixon, who promised to restore “law and order” on behalf of the “silent majority.” Nixon is held in contempt these days, even by many conservatives, but parts of his legacy deserve reappraisal. He acutely understood the threat of ideological revolution and anticipated the dynamics of bureaucratic capture.

Instead of viewing Nixon’s embodiment of the “imperial presidency” (a term invented to describe his aggressive use of executive powers) as a regrettable detour that led him to self-destruction, Rufo thinks Nixon’s only sin was to lose his war to the leftist elites that controlled the bureaucracy, the judiciary, the Congress, and the media:

Nixon believed that the federal government should provide a financial backstop for the American people, but he wanted to curb the power of the government’s experts, managers, and bureaucrats, who, he recognized, wanted to remake organic social institutions in the service of left-wing ideology. Nixon once asked his domestic policy advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan if his proposed basic-income program would “get rid of social workers.” Moynihan responded: “It would wipe them out.”

Alas, the same shadowy forces that confront American conservatives today managed to reverse Nixon’s 1972 landslide reelection, via what Rufo and his fellow Nixon fans are bold to label the “coup” of Watergate. Rufo tells Ward in the Politico piece:

“You see very clearly this pattern: that very powerful factions in the bureaucracy, the national security state, the media, the Democratic establishment and the judicial world were, in a sense, setting him up for a bureaucratic coup,” said Rufo. “[They used] his kind of culpability — especially the perception of his culpability — as a lever to take [the question of Nixon’s wrongdoing] out of the democratic process.”

And here’s the crucial kicker:

He added: “And I think we’re now seeing this with President Trump.”

The motive, it seems clear, for these appreciative backwards looks at the only president who resigned his office is to provide a justification for the only president who has been impeached twice. If Nixon was taken down by a “deep state” coup, then not only has Trump been justified in his past presidential abuses of power — he’s also justified in his plans for authoritarian vengeance if he returns to the White House in 2025. Rufo, for one, is pretty clear about that:

If we can rehabilitate Richard Nixon in the public mind, we will have demonstrated a capacity for reshaping how people think about political figures in the past, which gives us a lesson in actively shaping [the perception] in the present of political figures of our current day.”

And so you have Donald Trump as the second, and more successful, coming of Richard Nixon, who battled liberal elites on behalf of a “silent majority.”