Any serious student of history will tell you that pinning down the precise origins of great events is difficult at best, but one can often find important moments that offer a glimpse into their long-term origins. The Tehran Conference, convened eighty years ago at the height of WWII, is such a moment. Code named Operation Eureka, the conference opened on November 28th, 1943 and brought together the three Allied leaders, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet General Secretary (or as he is referred to in the notes of the meeting – Marshall) Joseph Stalin of the U.S.S.R. A close examination of the notes from this three-day conference gives us important insights into not just plans for the war itself, but possible origins of the Cold War that followed.

Planning for Victory

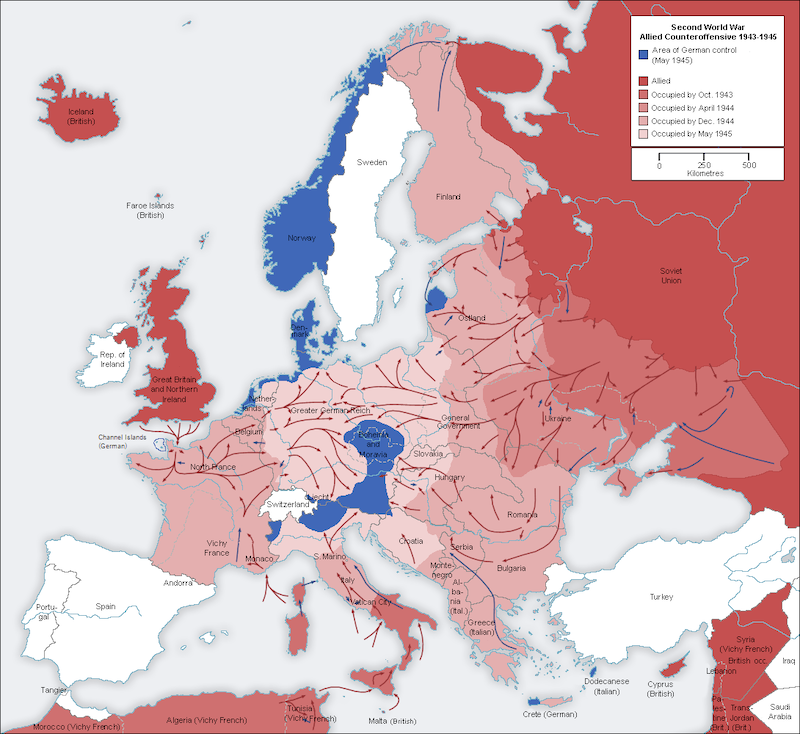

By the time the conference opened, the war had turned substantially, but not conclusively, in the Allies’ favor. The Germans were beaten in Africa, Fascism was collapsing in Italy, and the Russians had turned back Hitler’s ill-fated invasion and were slowly but steadily moving west. So, while one purpose of the meeting was to discuss plans for the conclusion of the war, notably the opening of a second front in the West, the status of Europe after the war, particularly regarding Germany and Eastern Europe, was also important. Drawing on the notes taken during the various meetings and private discussions held between November 28th and December 1st, we see the foundation of several of the Cold War’s most critical issues.

Stalin dominated the dinner meeting of November 28th and along with his animus towards Germany, he clearly didn’t trust France, asserting that their ruling class was “rotten to the core” and now “actively helping our enemies.” Both Churchill and FDR denied any intention to secure more territory for their respective nations, and both supported Stalin with regard to France. FDR suggested that anyone over 40 years old be eliminated from any future French government and that certain territories, like Dakkar and New Caledonia, be placed under the trusteeship of the United Nations.

The conversation then turned to Germany and again Marshall Stalin took the lead, although all three were in favor of its dismemberment. How long they expected that status to last is open to speculation, but it’s not hard to imagine Stalin planning for a lengthy Soviet occupation of some part of it. In the process of discussing future borders and the Soviet need for a warm-water port, two other future Cold War issues came up. First, Poland entered the discussion. Its eastern boundaries were to change to allow for a Soviet port on the Baltic, with recompense offered by extending (with Russian assistance) Poland’s western boundaries to the Oder River, which would restore German held territory to Poland. There was also a brief discussion of the status of the Baltic States, perhaps as a result of a translation. FDR suggested some sort of international state near the Kiel Canal to ensure free passage for all and the Soviet translator gave Marshall Stalin the impression the President was talking about the Baltic States themselves. Stalin quickly insisted that they had already voted to join the U.S.S.R. by “an expression of the will of the people” so as far as he was concerned, the subject was closed.

Personalities, D-Day, and the Future of Poland

After Roosevelt retired to his rooms in the Soviet Embassy (showing a trust in Stalin’s generosity few might have shared at that time) Churchill and Stalin continued the discussion. After attempting to draw a distinction between the German leaders and the German people, firmly rejected by Stalin, Churchill returned to the topic of Poland. Reminding the Marshall that Great Britain had entered the war as a result of its commitments to Poland, the Prime Minister agreed that the U.S.S.R. was entitled to secure its western borders but insisted that a strong and independent Poland was a “necessary instrument in the European orchestra.” He further proposed that the three leaders craft some fundamental understanding of Poland’s future status that he could take to the Polish government-in-exile in London, but Marshall Stalin was noncommittal. Did he already see the occupation of Poland as a long-term Soviet aim?

Perhaps inspired by Churchill’s strong position regarding Poland, Stalin lost no opportunity to take shots at him at the next dinner meeting on November 29th. He started off suggesting that the Prime Minister might harbor some “secret affection” for the German people and might be looking for a “soft peace.” The banter (characterized as both “friendly” and “lively”) continued as Churchill objected strenuously to Stalin’s suggestion that up to 100,000 members of the German Command Staff had to be executed to insure her continued weakness post-war. It is likely that Stalin’s comments were really aimed pushing Britain towards his proposed second front in Western Europe as Churchill was still arguing for his plan to hit Germany from the “soft underbelly” of Italy and the Balkans. But since Churchill and FDR had previously discussed the invasion they reassured the Soviet leader in a plenary session on November 30th that Operation Overlord was scheduled for May of 1944.

FDR and Stalin – Too Trusting?

At the same time, it is possible that Stalin’s actions and words had another purpose. He may well have been convinced that he could handle FDR more easily than Churchill and hoped to drive a wedge between the two. His conviction could have been inspired by Roosevelt’s own estimation of his relationship with “Uncle Joe.” In a letter to Churchill, FDR said he could “handle Stalin personally better than either your Foreign Office or my State Department. Stalin hates the guts of all your top people. He thinks he likes me better, and I hope he will continue to do so.” He even went so far as to request a private meeting with Stalin, linking his concerns about Poland with his electoral chances in 1944. He was concerned that any public suggestion to change Poland’s borders to benefit the U.S.S.R. would offend large portions of his constituency in the U.S. He also spoke in favor of referenda for the Baltic states, but reassured the Marshall that he was “confident the people would vote to join the Soviet Union.” It is difficult not to see FDR’s words as encouragement for Stalin’s expansionist plans.

In the political meeting of December 1st, the discussion turned again to the status of Poland and the post-war dismantling of Germany. Churchill resumed his argument that Britain entered the war because of Hitler’s invasion of Poland, though he also assured Marshall Stalin that the U.S.S.R. was entitled to secure western borders. Stalin asserted his desire to have friendly relations with Poland but drew a distinction between Poland itself and the Polish government-in-exile in London. He accused them of “slanderous propaganda” and the killing of partisans but said he could negotiate with them if they changed their behavior. At this point, Churchill suggested taking an offer to the government-in-exile, without telling them it came from the Russians, and told Stalin that if they refused the offer, “Great Britain would be through with them.” They discussed several variations on a specific border but made no firm commitment to one plan. As far as Germany was concerned, several plans were suggested involving larger and smaller collections of the German states. Everyone seemed to agree that Germany had to be broken up but again no definitive solution was reached.

Opportunities Seized and Missed?

At the end of three days, several important decisions were made, but some were also avoided, helping set the stage for 50 years of Cold War between the East and West. Operation Overlord was in motion, relieving some of Stalin’s fears of facing the Germans without more Allied help. Plans were also laid for Germany’s future, none of them firm and all of them giving considerable power to the Soviet Union, without a specific commitment from Stalin to the eventual freedom of that nation. The Baltic states were delivered up to Stalin on a silver platter and Poland got little if any protection in the conference, despite all of Churchill’s efforts. No one seemed to see the possibility of the U.S.S.R. taking all that territory and keeping it. Some of this failure must be laid at FDR’s feet. Did his belief in his ability to manage the Soviet dictator, combined with his worries about the next election, embolden Stalin to take and hold more than he might have? Three powerful and head-strong leaders gathered in Tehran for three days in 1943. How they each navigated these meetings goes a long way to explaining not just how they came to their final public statements about what happened in Tehran, but how the early seeds of the decades-long Cold War were planted.

Rusty Eder is a Teacher Partner with Teaching American History and the History Chair, Academy Historian and Dean of Faculty at West Nottingham Academy.